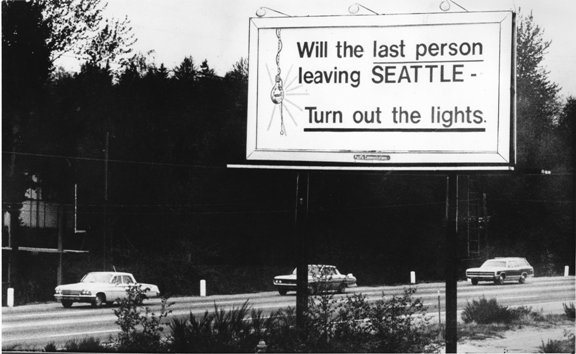

Architecture is typically focused on individual projects for individual clients, and therefore constrained within the many boundaries imposed: a specific site, program, zoning and regulatory limitations, the client's desires, economic limitations, etc. In this way, architecture is very limited in what it can hope to accomplish - impacting the public realm one project at a time, within pre-established constraints. In another sense, architecture engages with very large ideas about how society functions, and can achieve an impact at a larger scale than any single project. This is where architecture spills over into the realm of urban planning, politics, sociology, psychology, and culture. It's really the engagement with these larger ideas that excites me about architecture, as much as I love design in its own right. So it was immensely satisfying for me to see a group of the city's most engaged architects and urban planners come together to have - really to continue - a discussion that Seattle has been having about our current housing crisis.

As with any thriving major city, we have a shortage of housing, and especially affordable housing, which is driving rents up and threatening to push the middle and working class out of the city. I've written about this, and the Mayor's HALA recommendations, before, so I won't go in to that here. The Forum felt very much like a continuation of the conversation about the HALA committee's recommendations that the city has been having since they were released last summer. I've gotta say, it's nice to see a city - a group of people committed to the project of the city - having a conversation about how we should live: what the problems are and what solutions we can come up with. Architects are trained to identify problems, synthesize information and constraints, and come up with something that not only works, but is elegant, that fits just right - this is the essence of design, and it applies as much to civic concerns as forms and material choices.

One of the most compelling speakers was a (very entertaining) planner from UW Tacoma named Ali Moddares. Ali's presentation was rigorously data-driven - basically just a series of powerpoint slides of graphs and demographic maps that he animated with commentary. Ali identified a number of large scale trends affecting the region: a myopic focus on growth in Seattle and attendant neglect in the larger region (2/3 of all development in the region is in Seattle), the flight of young families from cities because of cost and the preponderance of studio and 1 BR housing types (which he called a "geography of age"), a very diverse but also highly segregated region, an enormous influx of commuters into the city everyday (as many as 1 million vehicle miles each way, each day from particular zip codes on the north and south borders of King County!). It all adds up to an image of fragmentation - a region increasingly segregated by age, income, race, and household size - in which everyone stills depends upon and commutes in to the city center for work, but increasingly can't afford to live there. It is a good thing that American cities are thriving, that companies are reinvesting in cities, that development is happening, and that people are choosing to live in cities, but this can come at the neglect of the larger entity, which is the region, leading to the placeless ooze of sprawl that has become so ubiquitous around American cities. Seattle's growth is Puyallup's sprawl, essentially - out at the periphery where farmland is being converted into endless, bland, unsustainable (but affordable) suburban sprawl.

The point Ali made is that there has to be a strategy for growth, implemented at the regional level, that combines job creation, housing, and transit. In order for the suburbs to be places in their own right, with real identities, and to reduce dependence on long, unsustainable auto commutes into the city, the suburban areas that ring the city must have jobs and economies as well as housing, and then be connected to the city center by effective mass transit, such as light rail. This hub-and-spoke system is essentially a rehash of the Garden City scheme Ebenezer Howard proposed in the 1890's. Howard's diagram clearly establishes a regional network of interconnected small centers radiating around a single larger urban entity. This concept relies on a regional balance of work, housing, and transit. The Garden City paradigm even included agriculture belts separating urban hubs - which may seem quaint now, but may also be due for a re-examination as local food production becomes an increasingly important component of sustainability and health.

Fig. Ebenezer Howard's "Garden Cities of To-morrow" Diagram, ca. 1898.

Why does this matter? These long-term planning decisions - growth management strategies enacted by some anonymous bureaucracy, enacted in such (still obscure) edicts as zoning codes and incentives may not seem like they matter much to real everyday people, but they really do. When we set priorities for regional growth, we decide how millions of people will live - people who most likely have no idea that any of this is taking place, people who may not live here or even be born yet, because the impacts of these decisions have effects that reverberate for decades to come. Growth and development planning determines who gets to live where, how much it costs to live, where jobs are, how long people spend commuting to work, whether they have access to parks and other amenities near where they live, whether the place where they live has an identity they can relate to and care about and invest in; it goes on and on - whether they feel refreshed or weary and frustrated when they get home to their kids after commuting, how easy it is for people without cars to hold jobs, whether the elderly can stay engaged in society when they can no longer drive, whether households can downsize to 1 or even no vehicles and rely on transit, how easy it is for teens who can't drive to socialize, and on and on. It has impacts on mental well being, social justice, sustainability, health, and quality of life. These big picture planning decisions literally shape the world in which we all live, which is what makes the engagement with these greater ideas so compelling to me. It feels meaningful, important, even powerful to think about and possibly someday have a real influence on the direction these background decisions take in basically defining the world the rest of us live in.

Some other ideas from the event:

- Policy changes to promote more construction of DADU's (detached accessory dwelling units - basically mother-in-law cottages), as a way to add density to single family neighborhoods without changing their character.

- Clustered housing with shared common space. One variation on this typology from David Neiman (which was really compelling - he's doing some great stuff) is a raised courtyard space shared by four townhouses above covered parking - all wood-framed, cheap, and easy to build.

- Microhousing - very small individual rooms (~120 SF) with shared bathrooms and kitchen facilities - as an affordable urban housing form that is currently getting a lot of NIMBY push-back in Seattle because it brings [perceived as poor, shiftless] people [ie. renters] into the neighborhood and threatens availability of street parking. These micro units in Seattle are renting for around $1000 right now (which is fucking unbelievable and should be a crime). But also, it is always about parking. Oh man, don't get me started on how much cars dictate everything that happens in our lives. People get really bent out of shape about their inalienable rights to drive a car whenever the hell they want at any time and find free parking.

- The idea of play streets - neighborhood streets shut down by the city one night/week for kids to come out and play in. (Also opposed by those who believe cars are sacrosanct). There is a similar cool thing called Night Out, where groups of neighbors register with the city to close down their streets and come out to have a party in the street one night/year - this started as a crime prevention strategy and is a really nice way to get to know your neighbors.

- The evolution of the NIMBY (Not-In-My-BackYard) who is theoretically in favor of development (just not anywhere near them) to a BANANA (Block-Anything-Near-ANything-Anywhere). The Major is getting a lot of push-back against density from residents of traditionally single-family neighborhoods, and I think it's brilliant that he's framing it as a social justice issue; basically if you say you don't want density, you're saying only rich people (who can afford an, on average, $650,000 single family home) should be allowed to live in Seattle.

- A really passionate and profound talk about acknowledging homeless people as individuals by architect Rex Holbein, who runs a non-profit called Facing Homelessness. Which I've thought about a lot, as I typically walk past maybe a half dozen homeless people on the way to work, but that I still can't exactly figure out what an individual should do in response to. Seattle is also in the middle of something of a homelessness crises - the latest One Night Count found 4500 individuals sleeping on the street. I tend to think more in systems than at the give-a-guy-a-buck-feel-good level, so I get all bogged down in what-is-this-really-doing vs. my baked-in Judeo-Christian do-as-much-as-you-can ethics vs. how much I am in debt right now vs. how good and easy my life is. It's complicated, right? Moral issues immediately become political for me, and that gets really complicated really fast. Anyway, if you know the answer, please share.

- Liz Dunn, who is an awesome local developer, emphasizing the value in adaptive reuse of older buildings to preserve character and create more interesting and desirable spaces (that still make money, but take more work, and are also more interesting). Also, the importance of incorporating small scale, fine-grained, local retailers instead of chain stores or branch banks (branch banks are the kiss of death to the public realm, fyi).

- Some other, more technical stuff that I need to learn more about: inclusionary zoning, tax-increment financing, rent control.

It was a planning-heavy event put on and attended by architects, which was good. We should be pushing our boundaries and trying to use our humble position in the food chain to do some good in the world. It was good to be in a roomful of people who really care about making their city and their world a better place, and are working toward that, small strategy by small strategy, project by project, reform by reform, tweak by tweak, and experiement by experiment.